Reyna Grande: The Other Side of Immigration

Reyna Grande, finalist for the National Critics Circle Book Award for her poignant memoir The Distance Between Us, will speak at SMU on March 19.

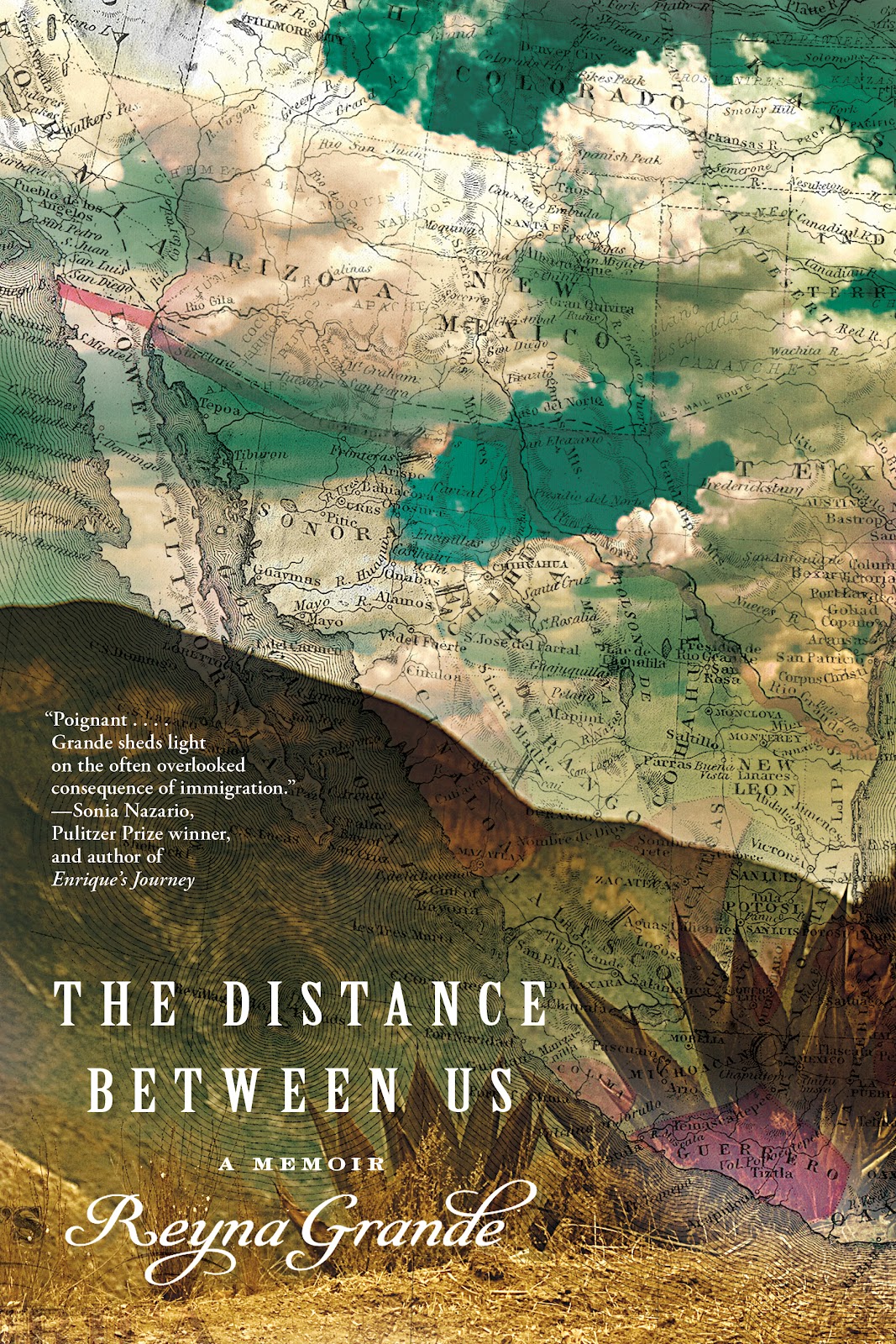

Reyna Grande, finalist for the National Critics Circle Book Award for her poignant memoir The Distance Between Us (Atria Books, 2012), will discuss “The Price of Being an American” — bearing witness to illegal immigration from an emotional and psychological perspective — at SMU at 6:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 19, in Dallas Hall’s McCord Auditorium. The event will be free and open to the public.

Department of English Professor Martha Satz recently reviewed Grande’s work for The El Paso Times. Following is an excerpt from that review.

By Martha Satz

Reyna Grande recounts a heartbreakingly sad account of her childhood in her memoir, The Distance Between Us, the anguish of which is magnified because she shares her fate with millions of other Mexican children.

Grande details a new contemporary psychological mythology, an inversion of the ancient Hispanic tale of La Llorana, the figure who steals children from their parents. In contrast, she catalogues the inverted dynamics of “El Otro Lado” (“The Other Side”), a villainous force that lures parents to desert their children. However, Reyna’s sad story is not only typical but also unique because she and her siblings are abandoned not only once, but sequentially—her parents leave and return only to leave again. And the children have been forsaken emotionally as well as physically.

Grande interweaves her tales with the fairytales she reads as a child to make sense of her life, “Hansel and Gretel” and “The Three Little Pigs.” She feels as alone and helpless as Gretel wandering in the forest and wonders if unlike the three little pigs she will have to face the wolf alone without the strong brick house and her father shielding her. Indeed, her life has an archetypal fairy tale quality of suffering. She and her brother and sister are left with a harsh and unloving grandmother, who indulges the other child living in the household, her cousin, while inflicting such harsh treatment on her and her siblings as dousing their hair with kerosene to rid them of lice.

This book is painful to read. It is full of the longing and desperation of the abandoned child for her parents’ love, denied her because of her parents’ ambitions to have a better life and because of their emotional and psychological inadequacies. Her father is an alcoholic, and her mother, left by her husband in the United States for a woman who is an American citizen, returns an emotionally depleted woman unable to love her own children.

Reyna Grande has proved herself to be a talented and poetic writer in her two published and critically acclaimed novels, Dancing with Butterflies, and Across a Hundred Mountains, but in this memoir she writes in a simpler and more straightforward way, evincing the language and viewpoint of the child. The emotional toll proves more exacting for the reader for its stark and limited childish perspective. Her words bore straight into the childhood self of the reader, eliciting an empathetic throb for an unanswered cry for love.

Discussions and headlines concerning illegal immigrants pervade our sensibilities. However, politicians and the public grapple with the issue on a macro level, discussing such things as economics and the labor force. But Grande gives her readers a different lens with which to view these matters, the very personal and familial one. Reading this book complicates and deepens our understanding of what immigration entails for all involved, and we can only be grateful for this writer who is willing to candidly reveal her grief, preserve an openness and acceptance of her parents, and graphically paint a picture of material and emotional poverty so devastating that it cries for our understanding and empathy.

###