Book banning in Round Rock

David Chard, dean of the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development at SMU, writes about the banning of TTYL by the Round Rock Independent School District near Austin, Texas.

David Chard |

Recently, my daughters were relating to me a real-life drama playing out in their school district, the Round Rock Independent School District near Austin. A middle school library acquired a book that doesn’t meet with the approval of some of the district’s parents.

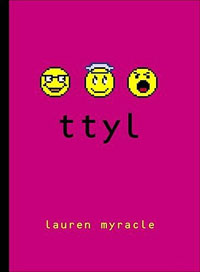

The book, titled ttyl and authored by Lauren Myracle, is about an adolescent girl who is being hit on by a 24-year-old teacher. From the excerpts I’ve read, ttyl appears to dance on the edge of adolescent thinking with liberally sprinkled profanity, sexual themes, and girls working together to support their friend, who is in a strangely exciting and dangerous situation.

Like many books aimed at adolescents, the book attempts to raise issues that girls at this age are thinking of and talking about: their sexuality, young men, and their futures. By the way, "ttyl" is instant-messaging lingo for "talk to you later."

The parents for whom this book has raised concern asked the superintendent to remove it from the library, and he did.

Removing books from libraries that were selected by librarians for a purpose is book banning. Book banning in public schools in Texas is not new. But this recent incident offers us the opportunity to discuss why banning this book is a bad idea.

Books that are aimed at a particular audience, in this case adolescent girls, often reflect issues that the audience is already thinking.

The result of this book-banning effort was that the books were bought and traded in a sophisticated underground market, people continued to talk about the exact issues that the government was trying to suppress, and the books were more popular and sought after than they may have been if they weren’t banned.

Secondly, banning books restricts the opportunity for people who aren’t part of the targeted audience to engage in conversation about the issues the books raise.

In the Round Rock situation, I believe parents should develop relationships with their children in which they are able to discuss the exact issues that adolescents are thinking about and described in ttyl rather than pretending that these issues aren’t already on their children’s minds.

At least one other important issue is that banning one book opens the door to every parent in the school district identifying books they think might be inappropriate for their children and therefore shouldn’t be in the school’s library.

We’ve seen districts attempt to ban the Harry Potter series, Catcher in the Rye, Fahrenheit 451, and almost any book by Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison.

In short, banning one book is a slippery slope.

Perhaps the most important issue this book-banning event raised in conversations with my daughters is not about the content of the book at all. They believe that parents should be more concerned about the quality of the writing in the books their children read. I agree. Good writing allows readers to build critical thinking skills.

Fortunately, my daughters can discuss the quality of the books they read because they have the freedom, opportunity and understanding to choose what they read and to discuss the ideas openly with their parents.

David Chard is dean of the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development at SMU. He’s reacting to the removal of a book in the Round Rock ISD. http://tinyurl.com/ttyl-ban