Two Methods for Applying Ethics

Method 1: Reflective EquilibriumReflective equilibrium is a process of moral reasoning that allows us to generate considered moral judgments about a case from a wide variety of initial beliefs and intuitions. At the early stages of ethical inquiry, the method can be used to explore and elicit various moral intuitions and beliefs. By focusing your attention on the factors in a case that are capable of justifying or changing moral beliefs, it is a useful way of exploring the morally significant factors in a case as well. Ultimately, the purpose of the method of reflective equilibrium is to reconcile, or move beyond, common conflicts amongst moral beliefs. 3All cases that are helpful for the exploration of ethics in a particular area contain such conflicts. These conflicts can be within our own set of beliefs (moral dilemmas), or between our beliefs, and the apparently reasonable beliefs of others (moral controversies).

We can call the inputs into the process of reflective equilibrium common-sense moral judgments (CSJs). 4CSJs are those claims that can reasonably made about the morality or immorality of various acts and situations. Common-sense moral judgments may be generated by reflecting on any or all of the three levels of moral thinking. They include general principles (we should try to be fair), theoretical claims (we should aim to maximize the utility for all affected), or basic intuitions (torturing kittens is bad). The process of reaching CSJs can be implicit or explicit.

The Process

- Considered moral judgments depend on reaching an equilibrium amongst all levels of moral inquiry. Reflective equilibrium is the process of reflecting on all three levels of moral inquiry to generate a coherent view. In cases where the different levels of moral thinking conflict, we adjust each level in order to achieve an equilibrium

- A level 3 general principle that conflicts with a wide range of level 1 cases, looks like an implausible general principle

- Particular case judgments that conflict with both 2 and 3 level principles, looks like a bad case judgment

- Mutatis mutandis for level 2 principles that conflict with level 3 and 1 claims

- We prune and adjust our views at all particular levels (and our considered judgments) until we reach an equilibrium

The aim of reflective equilibrium is to generate considered moral judgments about the case by beginning with these CSJs. The process of reflective equilibrium ensures that we take all levels of moral thinking into account in the process of reaching a considered moral judgment. Considered moral judgments are, in applied ethics, an appropriate standard for good moral reasoning. Therefore, if we do settle on a CSJ from one level of moral thinking, which conflicts with another CSJ without seeking to reconcile this conflict through reflection, we are guilty of bad moral reasoning.

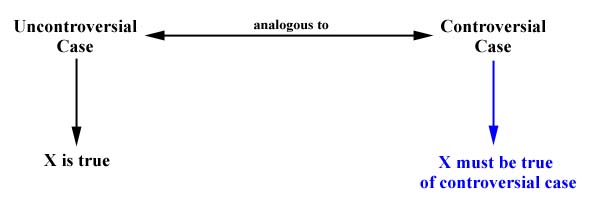

Method 2: Arguments by Analogy

Another good method for analyzing cases is to use an argument by analogy. An argument by analogy proceeds by finding some case that we can easily form a moral judgment about, which is relevantly similar to the problem case.

To make an argument by analogy you must be able to identify a clear or paradigmatic case that is relevantly similar to the case under discussion. For each course of action that could be used to resolve the problem case under consideration, identify another case in which that course of action would be clearly justifiable, i.e., identify a clear or paradigm case. You then need to compare the problem case to the paradigm cases. The idea is to weigh the closeness of the analogies between the problem case and the various paradigm cases in order to determine which option best satisfies the competing moral considerations. The strength of an argument by analogy depends on how good the analogy is, so the similarities and differences between the two cases are crucial. Specifically, the analogy will not work if there is a morally significant difference between the two cases.

Note there is often no single best answer moral problem cases, but this procedure is useful to both identify better and worse answers, and to highlight the morally significant features of the problem case.

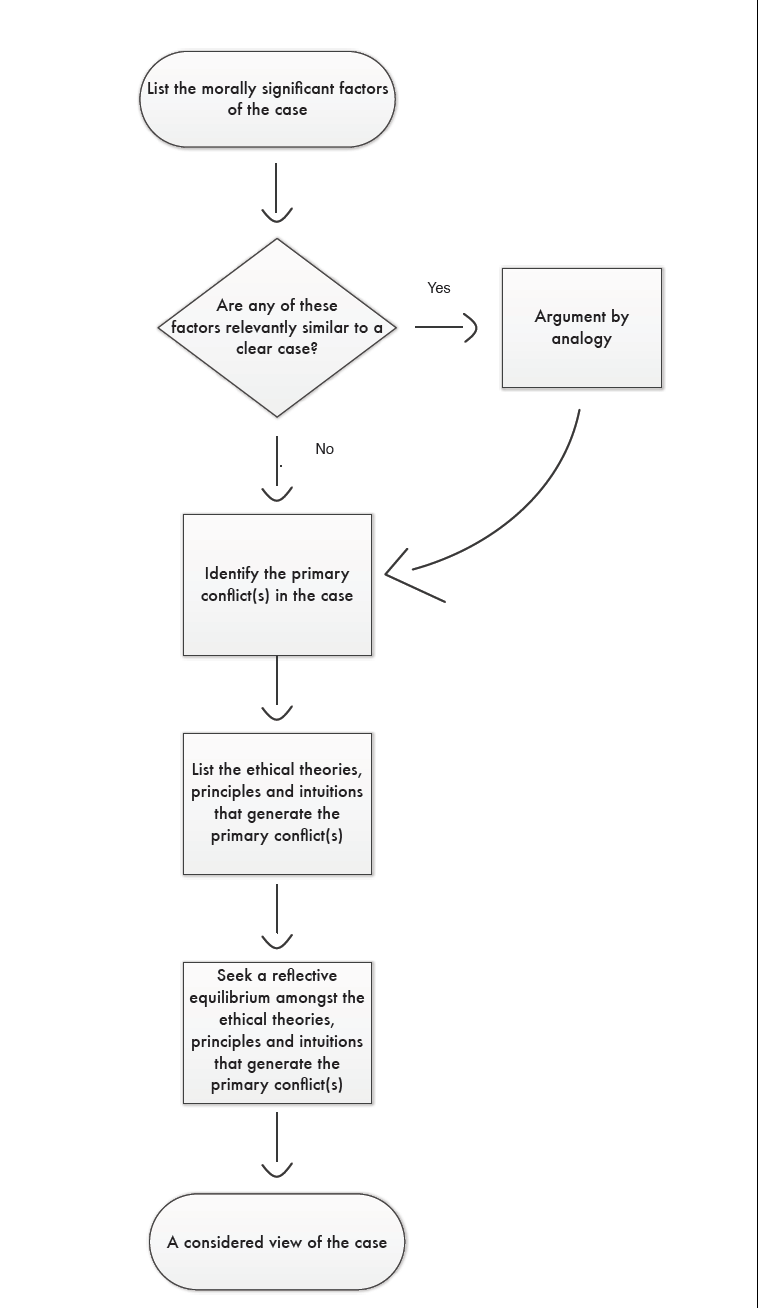

An integrated method for generating (more considered) moral judgments

Step 1: Identify the morally significant factors of the case. These are those features of the case that are capable of changing a moral judgment about the case.

- For instance, the intention of the person acting is often morally significant, as is the informed consent (or its absence), of those affected. In certain approaches to morality, such as consequentialism, the outcomes of the case are morally significant. There is no hard and fast rule for determining moral significance, the best practice is to begin by making the bar for moral significance low in the beginning, and then throwing out those features of the case that are not sufficiently significant.

Step 2: Test for relevant paradigmatic cases, if there is one, then make an argument by analogy, if not, proceed directly to step 3.

Step 3: List those ethical theories, codes or principles that are (or could) be used to justify one side of the competing moral judgments that are generating the conflict.

- Here you will generally be beginning with the list that you have chosen for your area, which are either specifically related to the area (i.e. the appropriate ethical code), or likely to yield relevant moral judgments in the area. (See the note on choosing your theories)

Step 4: Explore the intuitions of the class. What moral intuitions do people have about the case?

Step 5: Connect the intuitions to the various ethical theories and codes, to the extent possible.

Step 6: Try to reach a reflective equilibrium amongst the competing intuitions, theories, principles and codes.