New books from SMU’s Ezra Greenspan bring brilliant life, works of William Wells Brown out of obscurity

Prof. Ezra Greenspan has written a biography of brilliant and all-but-forgotten author William Wells Brown.

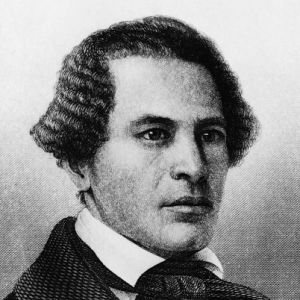

DALLAS (SMU) — Prolific writer and charismatic orator William Wells Brown (1814-1884) was a man of many firsts after escaping slavery: the first African American to write a novel, a printed play, a travelogue of his years as a fugitive slave living in Europe and three volumes of black history that included the first book about the experiences of African American soldiers during the Civil War.

William Wells Brown |

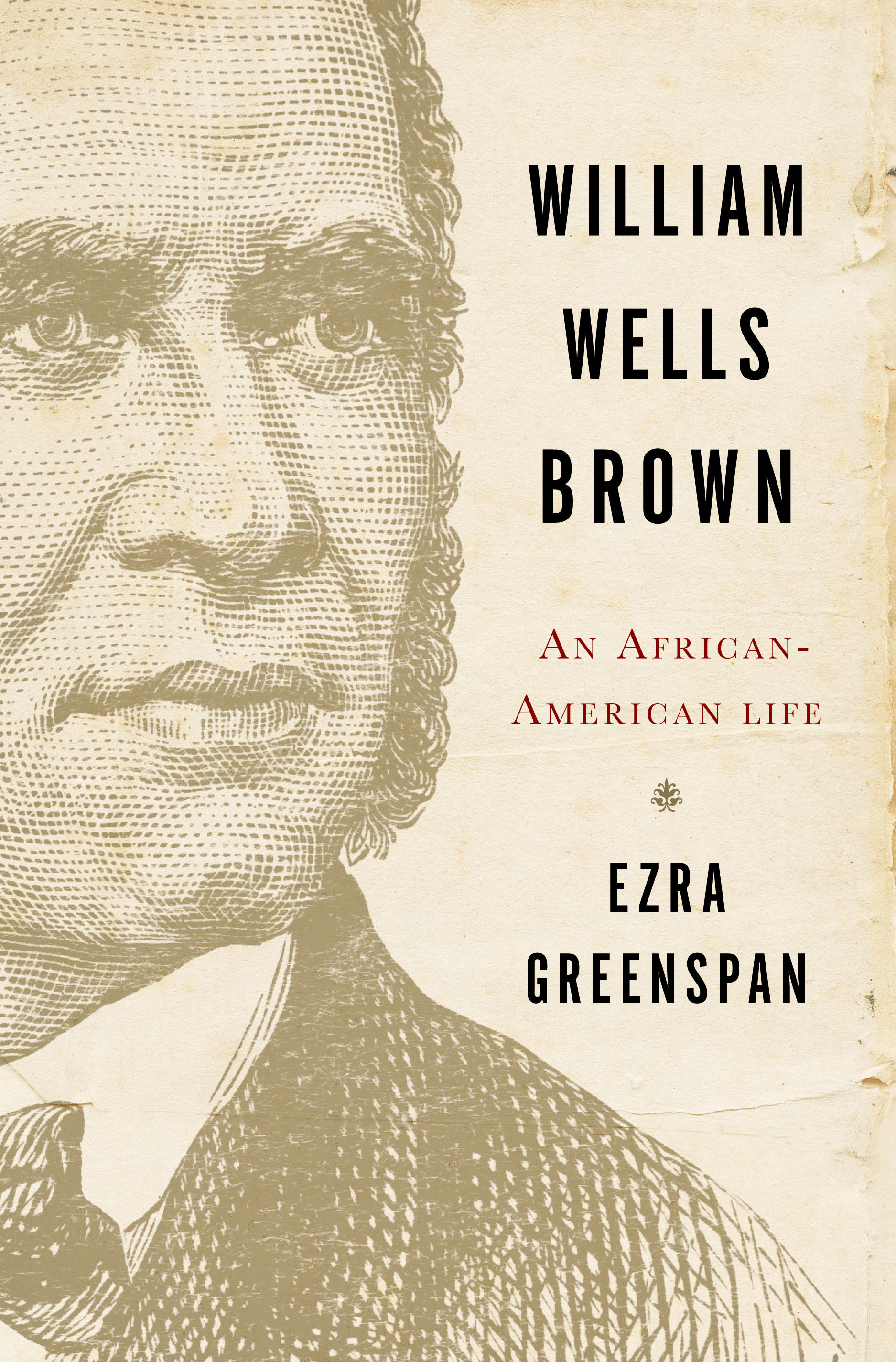

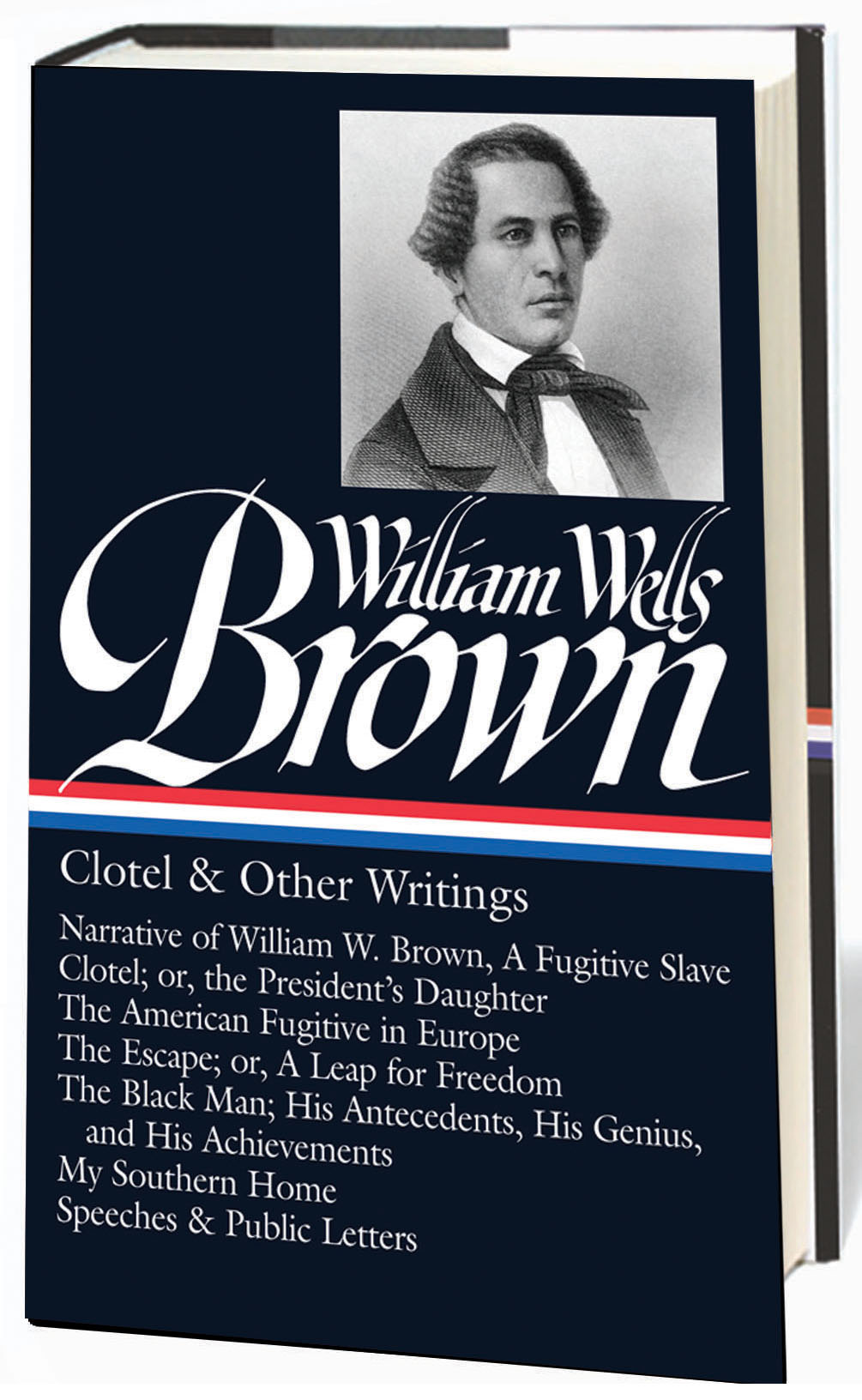

Despite his renown, Wells Brown’s work would nearly fade into obscurity in the Jim Crow era after Reconstruction. That’s changing thanks to SMU literary and cultural historian Ezra Greenspan, who is winning acclaim for two new books about the man he calls “the most rivetingly inventive, entertaining black writer of his era”: the biography William Wells Brown: An African American Life (W.W. Norton) and the 1,042-page anthology William Wells Brown: Clotel & Other Writings (Library of America), the most comprehensive collection of Wells Brown’s work ever published.

Wells Brown’s now-canonized 1853 novel, Clotel; or, the President’s Daughter, imagined the history of Thomas Jefferson’s black daughters and granddaughters, and did so while they would still have been alive. “He goes after the father of American fathers to expose the fundamental hypocrisy between Jefferson’s ‘all men are created equal’ creed and his actual practices,” says Greenspan, the Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Chair in Humanities at SMU. “This and other groundbreaking works by Wells Brown forced people back in the 19th century to ask hard questions about race, citizenship and civil rights we’re still asking today.”

|

|

Born into slavery near Lexington, Kentucky, to a mixed-race mother and white planter father (a cousin to their master), the light-skinned Wells Brown was given the name “Sandy.” He and his mother and six siblings ultimately moved west with their owner to live and work on a central Missouri farm adjacent to Daniel Boone’s. After having to be moved yet again, this time to St. Louis, his family would be permanently torn apart after being sold and “rented” to others, including in Wells Brown’s case, a succession of steamboat captains and slave traders.

A chance at a new and better life for Wells Brown came in 1834, when at age 19 he successfully escaped his final master’s steamboat while docked in Cincinnati (Ohio was a free state). As a fugitive evading capture, he would remake himself as William “Wells Brown” in honor of the Quaker friend who helped him to flee north to freedom. Living primarily in Cleveland, Buffalo and Boston, Wells Brown not only managed to lift himself out of illiteracy but also to use his talents to expose the atrocities and hypocrisies of the “peculiar institution” of human bondage when slavery was widely accepted in the U.S.

As an abolitionist, Wells Brown called himself “a soldier in this moral warfare against the most cruel system of oppression that ever blackened the character or hardened the heart of man.” As an “endlessly energetic, inquisitive, sociable” artist, Greenspan says, he would “skillfully unmask the hypocrisy of Christian slaveholders, exposing with startling intensity the violence slaves faced and the challenges of mixed-race people.”

Getting the full picture of the 19th century artist’s life would involve “a major act of research,” says Greenspan, noting that “somewhere along the way, Wells Brown had become an absence, an invisible man moving about in a world of recorded presence.”

Despite having written nonstop until the day he died, Wells Brown left behind no known personal archive — no family letters, diaries or correspondence of any sort, no working books, papers or library — just a few scraps of literary manuscript. By contrast, the archive for Frederick Douglass —Wells Brown’s great peer, and rival, with a similar slave-to-abolitionist life narrative—has more than 7,500 documents.

To fill in the gaps, Greenspan and his wife Riki visited nearly every place Wells Brown ever lived, also researching countless archives and scouring libraries with strong African Americana collections in this country and abroad — including the British Isles, where Wells Brown traveled some 25,000 miles between 1849 and 1854 while giving more than 1,000 talks.

Adding to the research challenge was Wells Brown’s penchant for embroidering the truth, which made it difficult for Greenspan to separate fact from fiction.

Ezra Greenspan |

Both Greenspan books are garnering praise from some of the world’s leading historians. Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., calls the Wells Brown biography a beautifully written and enthralling “experimental voyage” illuminating the 19th century dynamo’s “improvisational genius” while ensuring that Wells Brown’s “rightful place in the constellation of leading black men and women of letters will remain fixed for future generations.”

Greenspan received a head start on his Wells Brown scholarship when, while chairing SMU’s Department of English, he edited William Wells Brown: A Reader, in 2008. In addition to his work on Wells Brown, he has long been respected as a literary and cultural historian with particular expertise in the work of Walt Whitman and the history of print culture in the United States. Click here for more about his career.

# # #

Related Links:

- The New York Times: Sunday Book Review: ‘William Wells Brown,’ by Ezra Greenspan

- Salon: Escape from slavery: The harrowing story behind an African-American intellectual’s break for freedom

- The New Yorker: Briefly Noted: William Wells Brown

- The Texas Observer: Ezra Greenspan Rescues William Wells Brown from Obscurity in New Biography

#21140-nr-11/12/14-dg