Journalism Division Receives Iconic, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Photograph of Ruby Shooting Oswald

Alumnus Bob Jackson's iconic photo of Ruby shooting Oswald has been donated to SMU.

Members of the Dallas Press Club were cleaning out their storage unit last winter when a large photograph caught their attention.

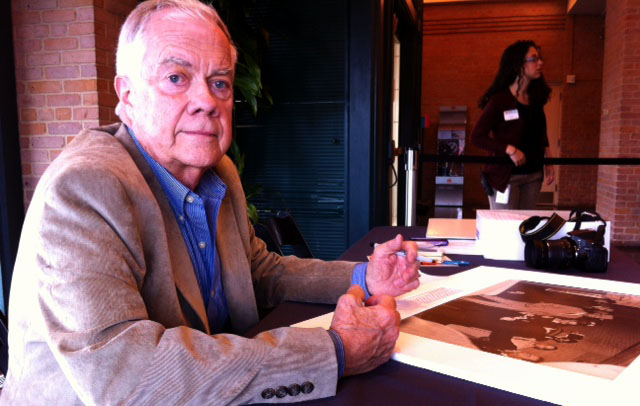

Tony Pederson with iconic photo of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald, by Dallas Times Herald photographer and former SMU student Bob Jackson. |

It was a picture of the moment when Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald in the basement of Dallas police headquarters on November 24, 1963. Taken by former SMU student Bob Jackson (1952-57), who was working for The Dallas Times Herald at the time, the photograph won the Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for News Photography.

According to Dallas Press Club President Liz Oliphant, Jackson donated the photograph to the Club shortly after the assassination.

“The photo hung in the Press Club for a long time,” says Oliphant. “When we no longer had club facilities — around 2005 — it went into storage along with many other mementos. When we discovered the photo, we donated it to the Journalism Division at Meadows.”

Professor and Belo Distinguished Chair in Journalism Tony Pederson says the photograph has historic significance.

“When you think about the assassination of John F. Kennedy, there are certain images that are iconic in terms of representing what happened in those days in Dallas and this is one of them,” says Pederson. “The image is extremely violent, but it does represent in a very real and graphic way an awful time in the history of the city of Dallas and of the United States.

“This photo also marks a time of significance in news coverage. It changed journalism in Dallas; it was the first Pulitzer Prize won by a Dallas newspaper. It was taken during a time when television was coming of age as a medium, and it did in those three or four days as events unfolded. It created an awareness of professional journalism.”

The missed photo…and the one that caught it all

On November 22, 1963, Jackson was assigned to photograph President John F. Kennedy’s visit in Dallas. Jackson and several other members of the media rode in an open press car in the motorcade, eight cars behind the president through downtown Dallas. His plan was to capture photos of the ride and then, at the corner of Main and Houston, toss his rolls of film to coworker Jim Featherstone, who would rush the film back to the paper in time for the afternoon edition.

Jackson shot several photos along the motorcade route using a long lens, and as the press car approached the appointed intersection – the same intersection as the School Book Depository – he unloaded the camera, slipped the film into an envelope and tossed the envelope to the waiting Featherstone. In a November 22, 1993, interview with the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas, Jackson described what happened next.

“As we rounded the corner … the wind caught the envelope and blew it out of his hands, away from him, and he had to chase it. … We were laughing at how he had to chase my film across the street. We had already made the turn from Main onto Houston, which put our car directly facing the Book Depository. We heard the first shot. … [fellow newsman] Tom Dillard and I looked at each other; the first thing we thought was, it could be a gun. Then we heard two more shots closer together.”

Jackson looked toward the sound, which came from the direction of the School Book Depository.

“I saw two black men leaning out of the window of the fifth floor, looking directly up above them. My eyes went on up to the next floor, and there was a rifle. I could see the rifle and part of the stock, and it being drawn in the window. … The person behind it was not visible. There was no one standing in the window or anything looking out... I said, ‘There’s a rifle’ and pointed up; Tom [fellow reporter] swung his camera up and he did photograph the empty window. Of course, I had an empty camera. I swung my camera up too, just so that I could see better with a long lens, and zoomed in, and no one was visible in the window. No one else in the [press] car saw the rifle. I don’t think I could have reacted fast enough to get a picture even if I had had film in the camera, because I saw it for only that short a time.”

In an interview for the 1999 Turner Network documentary “Moment of Impact: Stories of the Pulitzer Prize Photographs,” Jackson says he knew he had missed several pictures that would have been of historical value. But he stayed on the story and went to Dallas police headquarters where Lee Harvey Oswald was held and being charged with the assassination of Kennedy.

“The halls were crammed with people. It made it hard to even click the shutter,” said Jackson. That day, he managed to get a photo of Oswald’s wife, Marina, and Oswald’s mother as they stepped off an elevator.

On Sunday, Jackson was back at police headquarters, intent on getting a photo of Oswald being transferred to the county jail.

Bob Jackson signs the iconic photo as part of a Press Club event. |

“I felt like the basement of the police station might be the only chance … to get a photo of Lee Harvey Oswald,” said Jackson. “I walked right in, no security to speak of, nobody checked my press pass or anything.”

The parking garage was full of reporters. Jackson chose a spot across from the door where Oswald would emerge. “My plan was to shoot a picture as they brought him out into an open space. I pre-focused on about ten feet where I knew he would be in an open area. They said, ‘Here he comes,’ and as they brought him out he was handcuffed to two officers.

“As soon as he stepped into the open area I was aware that somebody was stepping out from my right. My first reaction was ‘this guy is getting in my way.’ Ruby took about two steps and fired. I guess I fired about the same time.

“Oswald just let out this very loud moan, it was a sound I’d never heard. Then it was bedlam. A policeman was shoving me back, had his hand over my camera.”

Because Jackson and the other reporters and photographers had been so close to the shooting, they were detained for hours as witnesses. Jackson knew he had to get his film to the paper as soon as he could.

“I thought I had something good. I wasn’t sure what it was going to look like until I looked at the film, but I felt like I had a good picture.

“When I walked into the newsroom, everybody said, ‘Do you have anything?’ Talk about pressure! When I held the film up to the light and looked at it, it looked good to me and it looked sharp. I remember letting out a yell and said ‘Yeah, I got something good.’

“I’m sorry that it all happened in Dallas but I’m glad I was able to record some of it. I think it took a long time for it to soak in, the magnitude of what happened here.”

In 2008, while reflecting on his extraordinary career, Jackson told members of the Sixth Floor Museum staff, "The Pulitzer Prize image will last a long time. I was just on a pretty routine assignment that turned into a historical event. I was just fortunate to be able to cover it. “

The photograph will be displayed at the east entrance of the Journalism wing in the Umphrey Lee Center, 3300 Dyer Street on the SMU campus.