On April 27, 2020, the Wall Street Journal published an excellent piece titled “A Secret Group of Scientists and Billionaires Pushing a Manhattan Project for COVID-19.” The piece outlined an effective partnership between private sector funding and citizen scientists to develop multiple waves of therapies, antibodies and vaccines for combatting the virus’s spread in an expedited fashion. Funding would come from the group members, and many of the scientists — including a 2017 Nobel laureate — resided at American universities. This group was doing what already could have been done earlier through federal, university and private sector partnerships: focusing on new areas of investment that have positive national implications. This needn’t be a monolithic industrial policy but must take into effect a new economic philosophy focused on the national, not just “multinational,” good.

As Jennifer Harris, senior director for international economics and labor on the National Security Council and National Economic Council, and U.S National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan state in a 2020 op-ed in Foreign Policy, “A return to industrial policy shouldn’t simply pick up where the country left off a few decades ago. Rather than focusing on picking winners in specific sectors, there is an emerging consensus that suggests governments should focus on investing in large-scale missions … that require innovations across many different sectors.”

Since the COVID-19 crisis began, many in higher education have been asked why the finest university system in the world wasn’t able to predict the crisis or provide a solution. While the question is somewhat unfair, more Nobel laureates in physics, chemistry, medicine and economics reside at American universities than anywhere worldwide — yet we weren’t ready. In addition, COVID-19 has pushed many already stressed university budgets to the breaking point. Failure to predict or address the COVID-induced environment highlighted much of the public’s perception of higher education’s flaws for survivability: that it has been disinterested in markets and relevance, distracted by politics, distrustful of public-private partnerships and disengaged from business solutions that could commercialize research for the greater good. According to the Education Advisory Board, which met for an Academic Affairs Forum in May of 2020, higher ed was an industry already at risk pre-COVID, with flattening growth markets and declining demographics, increasing problems with affordability and an uptick in college closures. With the pandemic, we have seen a dramatic drop in international students (and their tuition revenue), lower overall yields in freshman classes and an accelerating college closure rate. When the education industry is looking directly at a crisis, it is a good time to look for new solutions as a profession.

Higher education has reached an inflection point where its financial models are not sustainable, and its mission is being questioned by both the public and private sectors alike. Many public universities are subject to the calls of state legislators for increased efficiencies, yet operational efficiency is not a strategy, especially at a university. All cost-cutting does is buy time. American research universities do not need to change models that are based on core strengths of research and teaching — far from it — but they do need to find new, long-term sources of funding beyond endowments, federal grants and tuition increases. However, there is a significant disconnect between university research initiatives, market and societal needs and effective funding sources. Potentially impactful university research often lies fallow due to a lack of a commercialization culture on campuses and governmental restrictions on nonprofits. Leadership at research universities needs to undertake an overhaul of how they look at revenue generation and how they generate greater economic and societal impact in this new era. As observed in a study conducted by the Cleveland Federal Reserve between 1987 and 2013, this means a fundamental rethinking of our research agendas to have a greater impact and stronger partnerships with both internal and external investors. A university’s research independence should not result in academic isolation. It is time to find a meaningful and profitable balance, for the greater good.

The Bayh-Dole Amendment of 1980 went a long way toward allowing universities to benefit financially from federally funded research. A National Science Foundation report published in December 2022 indicates that the country’s academic institutions spent $89.9 billion on research and development in fiscal year 2021. This level of spending is a 4% increase from the previous year — with almost all of that increase funded by the federal government. According to the report, federal support accounts for 55% of research funding at all universities. But beyond Stanford, M.I.T., Notre Dame and a few others, American universities have been slow to adopt an entrepreneurial mindset toward the commercialization of technologies and IP — this despite the networks of corporate, private equity and venture capital funding that exist in many university business schools. Conversely, European universities are intensifying efforts to get promising ideas out of their labs and into commercial use.

As the Wall Street Journal reported in October 2019, universities in the UK, Germany, Scandinavia, Belgium, Switzerland and France are now scouring their labs for potential licensing and startup opportunities. While the main motive may be prestige and the public good, there exists the dual benefit of disseminating new technologies into society and creating an alternative source of revenue for colleges beyond tuition dollars.

In the future, we will likely see more universities looking long and hard at funding models far beyond tuition revenue, endowments and grants and toward the development of a meaningful research agenda that can also be commercialized to benefit those in need. Here, venture capital, private equity or private sector partnerships could make greater commercialization possible, but federal and state regulations regarding nonprofits should also be modernized to help facilitate these partnerships. This is particularly true in sectors critical to the national interest, such as biotech, supply chain technologies, pharma and alternative energies. John Hagel, of Deloitte’s Center for the Edge, which assists senior executives in making sense of and profit from emerging opportunities on the edge of business and technology, maintains that organizations creating economic value in the future will be the ones that find ways to participate more effectively in a broader range of more diverse knowledge flows that in turn refresh our commercializable technologies (i.e., research) at an accelerating rate. And that is where enhanced partnerships with research universities can benefit companies, universities and the economy.

Universities, either led by their business schools or with these schools as part of the forefront of the effort, should focus on three key areas in response to the changing landscape:

1. Similar to our national focus in the 1980s and 1990s on internationalization in our research and curricula, we should now focus on innovation as a primary driver of competitiveness, with particular emphasis on and support for areas in the national interest that will also help drive real wage growth here at home.

2. Through the better application of partnerships with the private sector, university research should be driven by its impact for the greater good and by the marketability of resulting products and technologies.

3. Universities, and in particular business schools, should actively invest in commercializable research from the university, new products and technologies created by the university and other public and private research centers. These investments should create new revenue streams for reinvestment into scholarships and programs.

The Cox Innovation Triad: The Why Side, the Make Side and the Buy Side of Innovation

The Cox School is extremely fortunate to have three key institutions that will serve our efforts to meet new economic challenges worldwide. Having three entrepreneurship institutes, much less on the same campus, is a differentiator for the Cox School and SMU. This Innovation Triad is essentially an innovation hub through which SMU Cox is building an entrepreneurship ecosystem to support our innovation vision. It addresses three key elements of business education: curricula focused on why entrepreneurship and innovation are critical to the future of business, the make side of innovation focused on building new, marketable business ideas, and the buy side of innovation, or the building of new leaders in the world of entrepreneurial investments.

The Why Side

The Caruth Institute for Entrepreneurship at SMU Cox, one of the nation’s oldest entrepreneurship centers, teaches our students why entrepreneurial thinking is so important to not only their careers but to the economy at large. The Cox School’s entrepreneurship programs, MBA Venture Fund, Blockchain Initiative, study abroad programs in places such as Berlin and Barcelona that expose students to new ways of thinking creatively and the Southwest Venture Forum are all ways our students learn how to be entrepreneurs, launching new businesses of their own or driving innovations inside their firms and organizations.

The Make Side

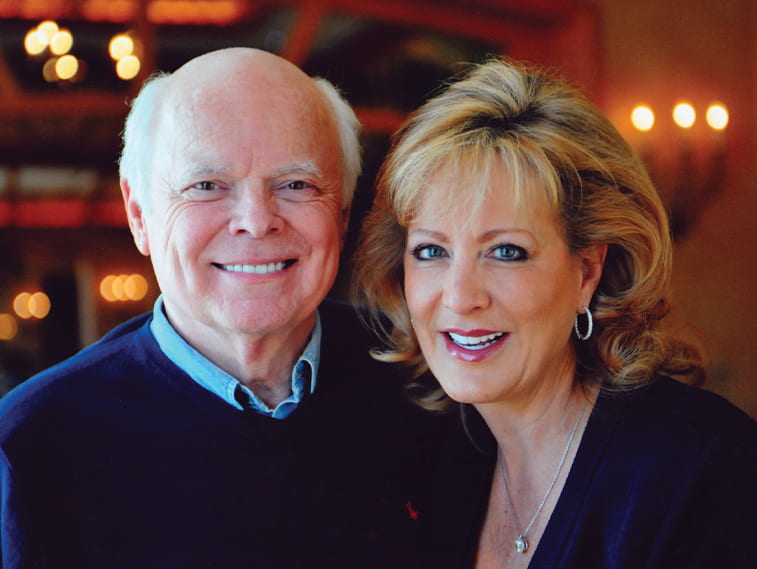

SMU Cox and SMU Lyle School of Engineering established the Hart Institute for Technology, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, or HI-TIE, as a co-venture in 2019. Founded through the gracious support of Linda and Mitch Hart, HI-TIE provides SMU students with the opportunity to build and create new products and processes for the marketplace and develop business plans to determine how best to take these products to the world. It provides the perfect blend of engineering and business students working together to produce and commercialize new technologies, innovations and research.

The Buy Side

The Cox School’s new Spears Institute for Entrepreneurial Leadership, founded in the spring of 2022 through a generous gift from Dr. William S. Spears, is designed to provide students with the talents to participate in the buy side of the new innovation economy, investing in university-driven R&D and building new pipelines for revenue. Similar to the Real Estate Impact Fund, this will create opportunities not only for students to invest in new ventures but also to generate earnings for the school to reinvest back into initiatives such as scholarships. It will also bring to Cox a world-class speaker series of business talent to help expand the dialogue. The Spears Institute will prepare students and create new ways for the school to invest in groundbreaking products and research.

As the newest branch of this critical Innovation Triad, the Spears Institute is still getting established, but in a rapidly evolving world, the timing couldn’t be better. Having the opportunity to learn all aspects of innovation will give our students a competitive edge like few business schools are positioned to give. Along with a curriculum that focuses on leadership, analytics and experiential learning, the Cox School is set to be a leader in business education innovation and entrepreneurship, preparing today’s students for the changing world of tomorrow.