Mrs. Shipley's Ghost: The Right to Travel and Terrorist Watchlists

SMU Law Prof. Jeffrey Kahn's new book raises questions about the constitutionality of watchlists.

By Denise Gee

SMU News

DALLAS (SMU) — Why is it necessary to provide your birth date and gender when buying an airplane ticket? It’s not a marketing ploy. It’s for the U.S. government to vet your name against a terrorist watchlist before deciding whether you can travel.

Jeffrey Kahn Hear Kahn's interview on KERA's Think  |

Most people are familiar with the No Fly List, part of the Secure Flight program run by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). What most don’t realize, however, is how similar the watchlist is to a system used more than 50 years ago – one ultimately deemed unconstitutional.

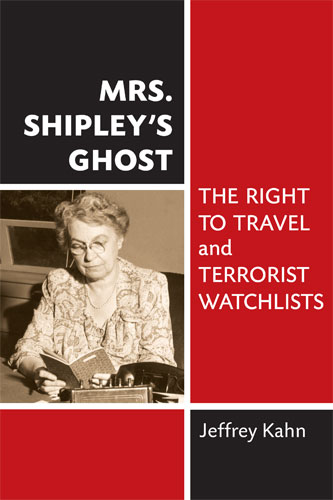

Will our current watchlisting programs meet the same fate or are courts now more willing to balance individual liberty with national security? That’s the underlying question posed by the new book Mrs. Shipley’s Ghost: The Right to Travel and Terrorist Watchlists (University of Michigan Press). Jeffrey Kahn, an associate professor at SMU Dedman School of Law, wrote the book based on research at the National Archives and interviews with current and former government officials.

Kahn’s book combines history, policy analysis and the law, beginning with an introduction to the No Fly List’s “intellectual ancestor”: Ruth B. Shipley. Her Mayberry-esque “Aunt Bee” appearance belied the immense power she wielded as chief of the U.S. State Department Passport Office from 1928 to 1955, when she almost single-handedly decided which Americans could travel outside the country and which would be kept at home.

Shipley’s work was especially important during the Cold War, when the communist threat to national security was feared as much as the terrorist threat is today. She was well aware of FBI reports and intelligence estimates of the risks posed to the homeland, from propagandists to saboteurs to terrorists carrying suitcase nukes.

While amassing files on more than 12 million U.S. citizens, Shipley identified those whose travel was, in the idiom of her day, “not in the best interest of the United States.” Her dedication was commendable, though her decidedly steely style prompted one of her bosses, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, to call her “a wonderful ogre” – as a compliment.

The average American dealt with Shipley’s passport regime without incident, just as most Americans today think nothing of TSA’s Secure Flight program or the FBI’s No Fly List. But when such celebrated U.S. citizens as Paul Robeson, Arthur Miller and Linus Pauling were refused permission to travel, it was entirely her call to deny them due process.

At least in Shipley’s era, those denied the ability to leave the country knew where to take their protests – to the “wonderful ogre.” The same isn’t true for those identified as security risks by today’s No Fly List, which Kahn reveals to be a remote, multilayered system operating in secrecy and without adequate forms of redress.

Kahn does not contest the government’s need to investigate terrorist threats, but “before the government can stop a citizen from freely moving about, our constitutional tradition has always been to provide notice and a chance to be heard,” he says.

Meanwhile, the number of names on watchlists continue to increase, with the No Fly List growing from 10,000 names in 2011 to 21,000 in 2012, reports The Associated Press.

“When confronted with the criticism that their power is too broad to be so unchecked, the keepers of these lists always answer in the same way: Trust us,” Kahn says. “Those officials cannot be allowed to decide, all on their own, which citizens may travel when and where and how. That is not how a democratic republic interacts with its citizens.”

By the mid-1950s, the courts began to demand that Mrs. Shipley provide a meaningful appeals process. In a similar vein, Americans today have responded to the No Fly List by taking their cases to court. In late June, oral argument will be heard in U.S. District Court in Portland, Ore., on some crucial motions in one of the most important cases, Latif v. Holder. The plaintiffs in that case, some of whom are U.S. military veterans, are demanding the same protection for their right to travel that Americans successfully wrested from Shipley’s control.

As Latif v. Holder is being decided, Mrs. Shipley’s Ghost recounts the history that very well might predict the future of the No Fly List.

###

#09998-nr-05/29/23-dg