Could Texas’ dirty coal power plants be replaced by geothermal systems?

SMU’s Geothermal Lab hosts an international energy conference focused on using heat from oilfields.

By Jeffrey Weiss

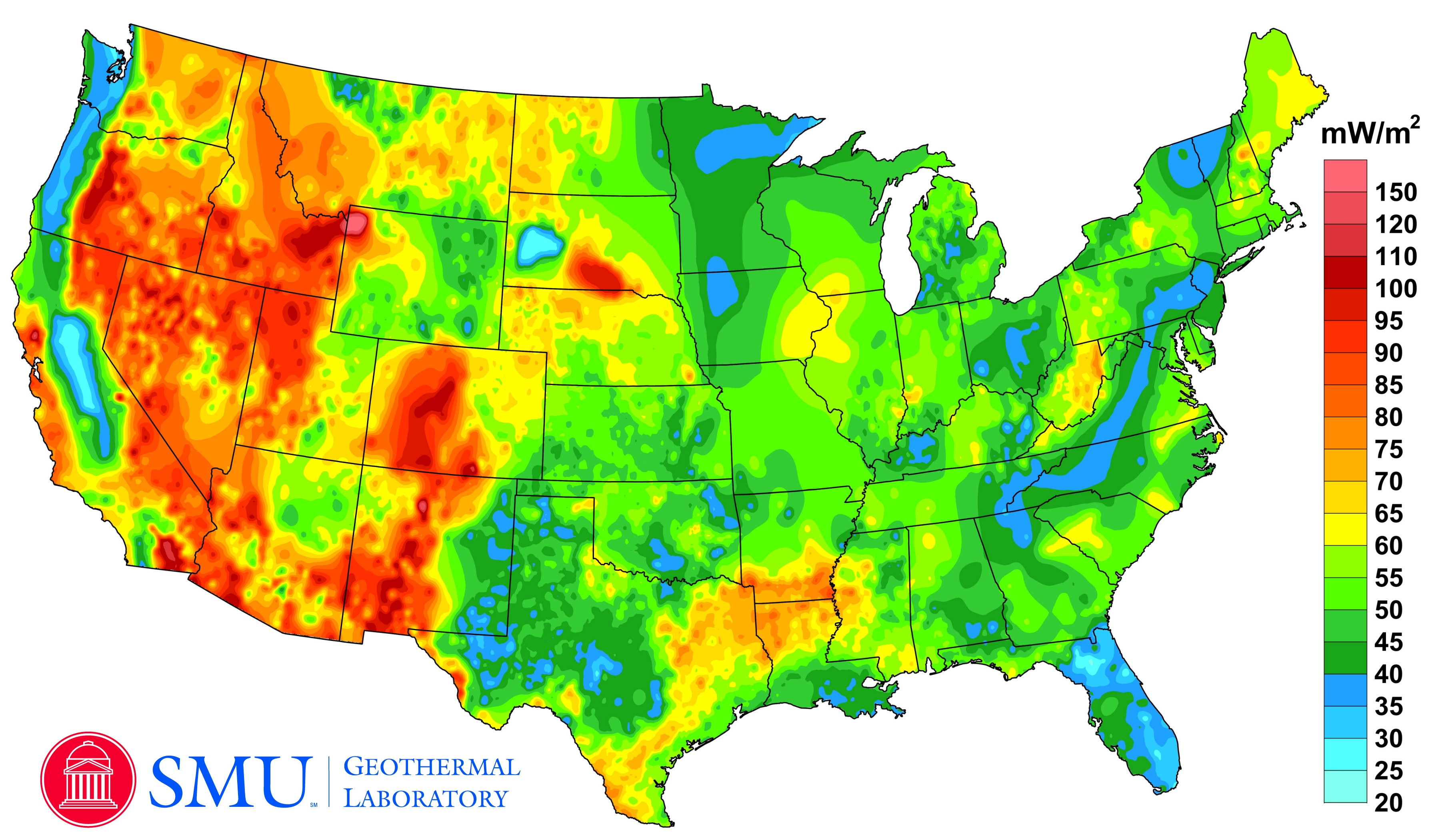

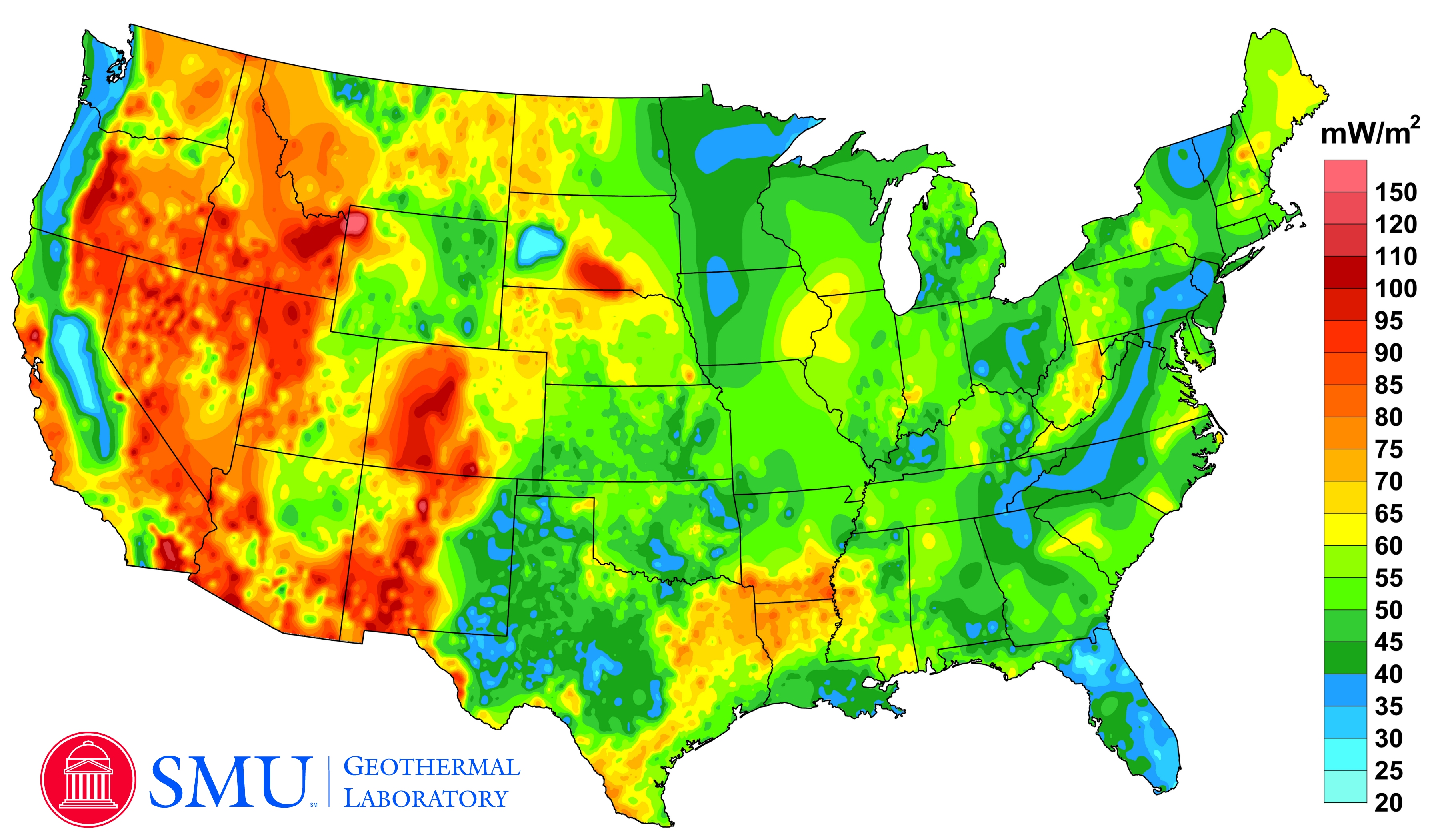

The SMU Geothermal Laboratory maps underground hot spots, including those in Texas.

|

DALLAS (SMU) – SMU’s renowned Geothermal Lab hosted its eighth international energy conference April 25-26 on the Dallas campus, focused on using the oilfield as a base for alternative energy production through the capture of waste heat and fluids. In addition to oil and gas field geothermal projects, experts discussed coal plant conversion for geothermal production, the intersection of geothermal energy and desalination, and large-scale direct use of the energy source produced by the internal heat of the earth. The technology that is the primary focus of “Power Plays: Geothermal Energy in Oil and Gas Fields” takes advantage of an existing resource frequently considered a nuisance – wastewater produced by oil and gas wells during extraction. As a well ages it will typically produce more water and less oil or gas over time, which raises the cost of production. Where the produced wastewater is hot enough, and the water flow rate is sufficient, specially designed turbines can draw geothermal energy from the wastewater. That “bonus” geothermal energy can be used to either generate electricity to operate the oil field equipment and lower the cost of production, sell the electricity directly to the power grid or – more likely – to nearby industry users seeking a highly secure electrical source. SMU’s Geothermal Lab team members are leaders of academic data sources for exploration and assessment of existing and potential geothermal resources. SMU scientists developed the Geothermal Map of North America and built one of the primary nodes of the National Geothermal Data System (NGDS) for temperature and oil/gas data. Their research efforts include over 50 years of continuous thermal data collection and is viewed by the community as an important first-stage resource used in determining the potential for geothermal energy production in the United States. The SMU Geothermal Lab has been the recipient of approximately $10 million in research grants from a variety of sources, including the Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, the Texas State Energy Conservation Office, Google.org and private industry. ### |

For Texas electricity customers, geothermal energy is pretty much an afterthought. But some scientists — and even some people in the oil and gas business — say that heat from deep underground may become a significant source of power.

At least, that’s the message at a conference held today at Southern Methodist University, hosted by the school’s geothermal laboratory. The event pulled together an unusual mix: Academics, oil company bosses, people hawking heat-transfer equipment, geothermal experts and a few environmentalists.

This was the eighth such conference held at SMU since 2006. Those who have been to several agreed that the biggest difference over time is that the presentations have shifted from blue-sky theory to some data from working projects.

Perhaps the loudest applause for the day was when Will Gosnold of the University of North Dakota ended his talk about a demonstration project with a slide of an email saying it had started generating electricity today.

Another presenter suggested that geothermal power could be an economically sensible replacement for existing coal-fired power plants, particularly if the existing power plants and their transmission lines are near coal mines. That’s the case in Texas.

Susan Petty, president of Seattle-based AltaRock Energy, told the group that many older coal plants will be unable to meet clean-air requirements and will need replacing in the next few years. Waste water used in coal mines could be injected into wells where natural heat would make the water hot enough to drive geothermal power generators, she said. . .

Geothermal power has some advantages over other renewables. The earth stays hot whether or not the sun shines or winds blow. But the current economics of energy production make geothermal growth a hard sell. Oil and natural gas remain relatively cheap. Wind and solar power get some special tax breaks.

In spite of that, the tone at the conference was generally upbeat.

“We all care about the earth,” said Maria Richards, the SMU geothermal lab coordinator, in welcoming the attendees. “We are applying knowledge that is applying hope.”