40th anniversary of occupation of Wounded Knee:

A new look at unlikely partnership

Forty years ago members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) were in the midst of a 71-day occupation (Feb. 27-May 8, 1973) of the tiny town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. “Wounded Knee penetrated the national consciousness in a way no other protest had,” said SMU history Professor Sherry Smith.

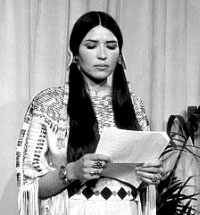

Sasheen Littlefeather |

Forty years ago members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) were in the midst of a 71-day occupation (Feb. 27-May 8, 1973) of the tiny town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, supported by an outpouring of sympathy from movie stars like Brando, mainstream churches, hippies, college students and housewives.

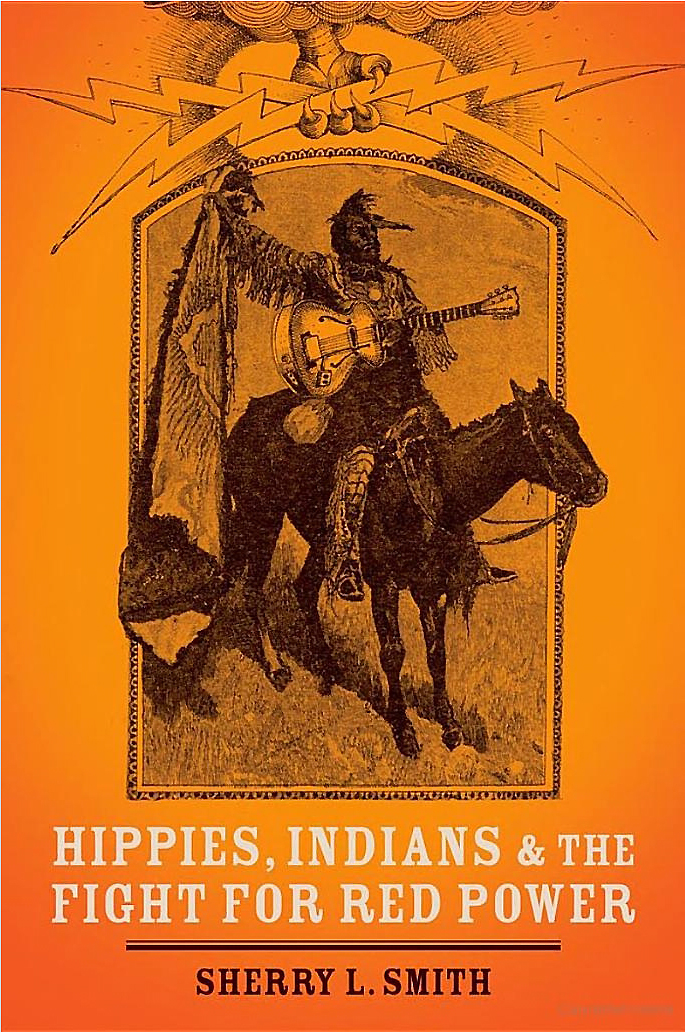

“Wounded Knee penetrated the national consciousness in a way no other protest had,” said SMU history Professor Sherry Smith in her new book, Hippies, Indians, and the Fight for Red Power (Oxford University Press, 2012).

The occupation of Wounded Knee was a turning point in Native Americans’ fight for self-governance, Smith said, but its success was partly the result of an unlikely alliance of a hodgepodge of supporters ranging from hippies to Methodists to Hollywood celebrities. Smith’s book is the first to examine this alliance that cut across racial, ethnic and class lines. She devotes part of the book to the Wounded Knee occupation.

“I felt this story had not been told,” says Smith, who devoted 10 years to writing the book. “The primary figures in the Red Power movement – the most important movers and shakers – were Native Americans. But the support they received from non-Indians was a critical, even essential, component in their ultimate successes.”

American Indian Movement (AIM) leader Russell Means and U.S. Assistant Attorney General Kent Frizzell, sign an agreement to end the Native occupation of the historic village of Wounded Knee. South Dakota. |

“Hippies were among the first non-Indians of the postwar generation to seek out contact with Native Americans, learn about their grievances, and join their call for reform,” she says. “They did so in large and significant numbers, which in turn caught the attention of the rest of the nation.”

To tell the story, Smith interviewed non-Indians involved in the alliance such as Stewart Brand, creator of the Whole Earth Catalog; actor and counterculture activist Peter Coyote, as well as Native Americans such as Joe Sando of the Albuquerque Pueblo Cultural Center . She also relied on sources ranging from the Richard Nixon Presidential Papers to the American Friends Service Committee.

Smith links the interest in Indian affairs in the 1960s and 1970s to cultural events, such as the 1962 publication of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which featured one of the first prominent fictional contemporary Indian characters, Chief Broom. In addition, Dee Brown’s 1970 bestseller, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, opened readers’ eyes to the root of Native American demands with the first history of the American West told from the Indians’ point of view.

“I was very impressed with those individuals and groups, including the church-based organizations, that rose to the occasion and helped push for substantive reform in Indian policy in the 1970s,” Smith says. “This was not about them, but about others. They had nothing to gain personally, other than a sense that the nation was finally living up to its promises.”

Can it happen again?

“We have become increasingly fragmented in this country,” Smith says. “I think our nation has been in a reactive state for 40 years now, turning away from the turmoil and challenges of the Sixties. But I am heartened by the resurgence of activism. It is certainly possible and even probable that social and economic justice movements will be revitalized. “

About Sherry Smith

Western historian Sherry L. Smith is professor of history at Southern Methodist University and associate director of the Clements Center for Southwest Studies. A former president of the 1,300-member Western Historical Society (2008-2009), she has published four books and numerous articles on race, ethnicity and Native American policy in the American West. Her honors include fellowships from the Fulbright Foundation, Yale University, National Endowment for the Humanities and the Huntington Library.

Sherry Smith

Listen to her interview

on Native America CallingSmith was a high school and college student in the Midwest during the 1960s and ‘70s where, from afar, she was sympathetic to Indian demands for justice and fascinated by the hippie movement. She considered contributing to the Native American movement by becoming a lawyer specializing in Indian law, but decided instead to make a difference by becoming a historian and educator.

“The ‘60s and ‘70s were an amazing time in this nation’s history – the turmoil could be distressing, particularly when it turned violent, but the challenges to the status quo and the demands for justice from many quarters was exciting. There was strong feeling – even in the American Midwest –that change for the good, that social justice, was possible,” she says.

# # #